If you’ve read the preceding articles on author-focused play in tabletop role-playing games (herein TTRPGs to save my typing fingers) you’re probably wondering how the hell all this authoring can go on and it not be absolute chaos? Or how the hell does the GM introduce any sense of an intentional plot?

We are going to consider this in two articles: –

- How The Table ‘Plots’

- How The GM ‘Plots’

There may be a third-part where I give an end-to-end example using the most recent campaign, but we’ll see if that’s necessary by the end. This is the first part which deals with how everyone at the table ‘plots’ in this crazy author-focused environment.

It’s Important Everyone ‘Plots’

The flow of and what constitutes the plot is decided by everyone at the table, as you’d expect from an author-focused play approach, but it’s not chaos. Yes, some games have rules embedded in the system to control and navigate this chaos and some don’t (such as Dungeons and Dragons) but the principles are the same whether they are in the rules or not.

What I’ve tried to do here is show how I took a load of advice I’ve absorbed across many games and TTRPG discussions and turned them into something I could make actionable. In doing this my consultancy brain kicks in and I end up codifying and framing things in a way that is consistent and actionable. It builds on the work of others and I am sure other people are doing variations on it.

I’ve consolidated my approach into two sets of high-level themes which I action and keep in mind constantly at the table. The two sets of themes cover How The Table Creates Plots and How The GM Plots (to be covered in part two).

Proactive, Competent And Dramatic

There is a key dynamic to author-focused play and that is your characters are proactive, competent and dramatic and your players know it and work it accordingly. These are key factors that contribute to how the table as a whole ‘plots’. The game Fate specifically states this as a facet of its design and it holds true for all author-focused play. If your players are reactive and not proactive, you have characters that are made to look incompetent and the characters lack drama (a story to push) it’s safe to say this approach will not work.

Characters should be proactive in how they solve problems. Ideally, they’d have a range of abilities to do this in the actual game. The players should recognise this and they shouldn’t be sitting around waiting for solutions to present themselves from another source. Let’s face it, that ‘other source’ invariable means the GM. The more that happens the less we’re talking about author-focused play and it becomes more GM-led. Your game should give clear, open opportunities for players and their characters to proactively advance events.

In an author-focused game, characters are competent. They are quite often good at what they do and they are also valid, card-carrying members of Homo Fictitious. They are not like us. They don’t bumble through life. They have a purpose and they are fully capable of rising to that purpose and facing the challenge. Not all may go their way, but they don’t fail at the inconsequential or the banal, they fail at what matters. Since the characters are members of Homo Fictitious they live dramatic lives. They’ve either stepped across the threshold of some grand tale or sit on the edge of taking that step. Possibly multiple times. The stakes are always high for them, society or the world at large. They constantly have to make important, difficult and consequential choices.

It’s because you have characters like these and players willing to play them that the whole table is creating what constitutes the plot.

How The Table Creates Plot

When considering how author-focused play actually happens at the table it’s all too easy to fall into all sorts of specific examples which sound very different and specific and aren’t really very helpful in communicating the what of things. It may even be quite obscure as to what is going on to the extent it’s hard to transfer them.

I tend to think all those examples, back and forth and the series of frenetic activities in play come down to three themes.

| Theme | Description |

| Signals | Signals of intent should be clear either via being articulated in play or due to being intentional on the character sheet. |

| Responses | Responses should be in the context of the signals and theme, mood and character(s) and plot in play. |

| Mediation | A respectful level of mediation should exist over who controls outcomes and how results are decided. |

Can’t Stop The Signal

Signals are very important and it is the absence of these that often makes author-focused play very hard. A lack of signals is a lack of communication. If it’s never clear what the intent, flavour and context of the story is, it becomes very difficult for everyone to author the how of it actually happening.

Signals are the nervous system at the table that allow author-focused play to happen. The absence of them is what causes it all to fail.

The Signal Nervous System

The signal nervous system exists at numerous levels and I believe it’s important to have intentionally layered this as early as makes sense. The end result is a very consistent and authentic set of layered signals.

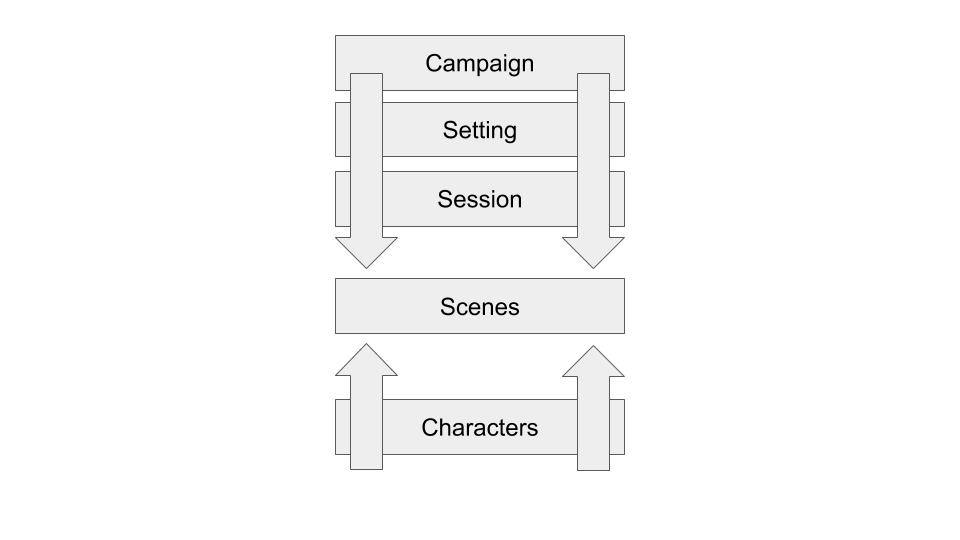

The network of signals comprises signals at the campaign and setting level which flow down to specific sessions. Signals embedded within the characters flow upwards. All this comes together in scenes which are the mechanism and construct in which author-focused play actually happens.

This may be one of the biggest changes in your approach to gaming when undertaking author-focused play, the fact everyone acknowledges scenes are a construct and uses them as the vehicle for how the tyres hit the road with respect to signals, responses and mediating that process.

Campaign and Setting Signals

Campaign and setting signals set the tone and theme of your campaign as well as the influences which act as a shorthand for communication. Is the intention for things to be deadly serious or comedic? Heroic or very gritty? Optimistic or pessimistic in tone? What themes does it play with? What video games, films, TV shows and novels can help communicate these things as a visual reference.

The other way to look at is, as a group, you are defining a common understanding of what success looks like.

You can establish these things in two ways. You can create a short pitch document or you can leave things for a session zero or do a bit of both.

A pitch document communicates some things upfront if you have a clear idea of some of the things that are important to you as a GM and the players need to buy into that to go ahead. Just keep it short. It’s quite possible to communicate all this stuff in 4 pages or less of not dense text.

This can also feed into a session zero.

Session zero is quite simple. It’s about everyone getting together before play to define all this sort of stuff. As an example, If the intention is to play a superhero game that leaves a lot to decide. The session zero would establish all that we’ve discussed about the campaign to establish what the comic book or animated series looks like and the appropriate characters for it, so they can be created and then you’d play characters together.

It’s my belief pitch documents and / or running a session zero are essential. Very few campaign concepts fully communicate their intention without digging into some of this stuff ahead of time. The important thing is to keep it at the intent level, not volumes of canonical fact details. A bit like a TV show you want to discover and establish the facts through play as you tell the story within the framework of the intent.

I tell you what you don’t want? To spend session after session with the people at the table trying to figure out or decode what the campaign is about. It wastes time. It means people can’t author within a context so they don’t, or what they author cuts across each other or worse things go gonzo pretty fast as things escalate with no commonly accepted throttles.

There is beauty inherent in everyone authoring under a shared understanding and a horror show without it. So make sure you have a common understanding of what success looks like.

Character Signals

Let’s jump to the bottom for now before we hit the middle where all these clash in the exuberance of at the table creation.

A perfect example of a character signal was discussed when we talked about how your characters aren’t normal and should be burdened with a premise. I do this for all my characters as a player. The mistake I make is it sometimes only exists in my head. I am seriously thinking of making it something all players need to outline in the future whether embedded in the rules or not. Explicitly.

A character’s premise is expressed in three types of conflict: external, internal and philosophical and the should inter-relate. As an example, we could say Luke Skywalker’s premise would be: –

External: Must defeat the empire.

Internal: Am I a Jedi?

Philosophical: Can good defeat evil without becoming evil?

Establishing a premise for every character and each player being aware of each character’s premise is one of the strongest and clearest signals. Since the premise is the story the character exists to tell it is the ‘big signal’ that characters go into an author-focused play game with. Everyone knowing allows them to respond to that signal or pro-actively work with each other’s premise.

Mediating Creation

We’re going to discuss the third principal now, as it’s useful to have it covered before we discuss responding to signals.

Creation is inherently destructive. So how do you stop a bunch of people creating at the table becoming chaotic, destructive of any sense of overall theme and context and descending into gonzo pretty fast?

If you have this as a concern you’re right to have it. If you don’t have it as a concern then you should. I’m a fan of author-focused play, fiction first games with rules embedded in the game to support it but one valid criticism of that approach is that in the wrong environment things can descend into crazy, gonzo, borderline comedy pretty fast as everyone escalates the contributions in crazy ways.

There is probably more to discuss in this area in terms of how authoring at the table and a sense of GM plot intersect, but we’ll save that for part two. For now we’ll concern ourselves with a wealth of creativity not destroying the game.

The first rule of mediating creativity is to address it as early as possible in the creation process.

Why? Because anything addressed early is something that the group as a whole has decided on and has moved forward with on a commonly agreed understanding they are excited about maintaining.

This is why pitch documents and / or session zero are important. They are the principal tools by which you start meditating early. The outcome of such processes is essential a shared understanding of the various throttles and dials that exist at the table whether you discuss them explicitly or not. Not having a commonly agreed understanding of them ahead of starting means people will author stuff that feels like it’s not from the same creative endeavour and that’s when the wheels fly off the vehicle (or is one main cause of the GM wrestling back too much control).

This common understanding and agreement on the various throttles and dials make the second rule much easier.

The second rule of mediating creativity is meta-game discussions are perfectly fine.

This is very important. It’s important because it is communication again. Conscious and explicit communication, not confused, unconscious and implied communication. You’re probably spotting a theme here about author-focused play by now? It’s all about explicit communication, understanding and agreement in ways that leave vast holes to be filled (which will get covered more in How The GM Plots) by not creating everything upfront.

This is why we said earlier one of the biggest changes you’ll make is recognising scenes consciously as a construct in your actual play as it acts as the vehicle for communication.

A player doesn’t just go to talk to the King, he wants a scene with the King for which there is probably a conflict that needs resolving or some discovery that needs to happen. These facts exist whether you address and communicate them explicitly or leave them implied to hopefully be figured out sometimes almost by mind-reading between the participants.

Since the scene is conscious you can set the stakes for the scene: what is at stake? Is it a conflict such as persuading the King to bring his armies in support? Or is it an act of discovery where it’s just information that is being sort (which can also be a conflict depending on if the King wants to reveal it)?

The setting of the stakes is where the mediation happens; all the signals roll up into it and it frames the potential responses. In setting the stakes the player will be going for an outcome related to signals in play be it those for the campaign, session or to try and move his premise forward – or possibly something else that’s come up in the session in relation to these things. In that way the stakes are being set in context.

The scene is played out, things may not necessarily go as intended, the dice decide success or failure (and the stakes will have set what failure actually is) and story direction and it all happens as an act of creation that adds to the whole rather than detracts from it.

Plot Is Responding To Signals

So how is the table plotting? The plot unfolds by pushing signals and responding to those signals in the context of the common understanding that has been established around the campaign.

The players respond in ways that move their character’s story, the story of another player, that is being built up over time and hopefully working towards resolving a clear signal in the form of the character’s premise.

The GM has the opportunity to respond to these many signals by taking the opportunity to insert the ‘plot’ he has in mind. While we’ll cover this in part two, the beauty of doing it this way is railroading doesn’t really exist for two reasons. First, anything introduced is within the themes of what’s been commonly agreed and, second, you’re responding to clear player character signals so anything introduced is by definition in support (which doesn’t mean it’s not a presented as a challenge or conflict) of said player character’s story.

This means they’re either commonly agreed ‘rails’ or ‘rails’ the player character is choosing to jump onto so much as ‘rails’ exist. Anyway, more on this in part two.

Do The Rules Matter?

Yes, but you can do this with any game as it’s more about an approach so it can work in any game. I think there is are two very high-level philosophies that need to be adopted and one works across systems better than the other.

Author-focused play can work across almost any system as while it’s handy to have signals embedded in the rules as actionable things at a system level, setting stakes and mediation guidance on outcomes, etc, it’s more a philosophy that the group can agree to adopt and just do as part of a social contract rather than it being a facet in the rules they are using. We’ve played games that embed such things in the rules and games that don’t, such as Dungeons and Dragons, and it works out fine in both.

A fiction first approach is half implied to be in effect when approaching author-focused play. Since you’re setting things up to explicitly discover and author a story it makes sense that your concern is the fiction in the game. So fiction first tends to mean what you take as your direction and what you are seeking to resolve is the fiction, not a simulation or actual real thing happening. As an example, when you set stakes in a fiction first game often success at the actual task is not what is at stake but the fictional outcome.

This is harder to do when the rules are fighting you. Some rules work on a fiction first principal, some work against a fiction first principal and some are relative levels of indifferent. Dungeons and Dragons isn’t a fiction first game but due to the way it works is largely neutral and you can overlay it or it has whole elements that can be used for fiction first purposes – the way HP is an abstraction, for example.

And, Finally…

I’m conscious this is only half of the story as to how this intersects with how the GM plots in this set-up haven’t been covered. We’ll cover that next in part two.

What’s important to take away from this is the power of communication and making things explicit. While not everyone needs or wants to take an author-focused play approach if you do what kills is it is not being clear and not being explicit about intent. Note I didn’t say being explicit about outcomes. At all times outcomes are to be found in actual play, but vague common understanding and communicating of intent just results in chaos.

That’s why clear signals are incredibly important, the rest is practice on how to respond to them in actual play by focusing on the fiction and stakes and working things on that basis.

But next is, how the GM plots without throwing a grenade into all this authoring at the table.

One Reply to “How The Table ‘Plots’”