This is the second part of a two-part article series that seeks to take a campaign that has been played to completion to demonstrate how various methods and approaches we talk about on social media and the web on a regular basis, including this very website, were practically used.

The first part covered all the contributions to the success of the campaign before the dice dropped, this article covers what happened when we started playing as the first handful of sessions defined the campaign.

Obligatory Disclaimer

The whole approach outlined here is dictated by one simple fact: the campaign’s outcome was an intentional story. This means if you have a different goal in actual play then it may limit some of the things you can take away from this article.

None of the ideas in this article are meant to be THE way just A WAY, at the same time I’m not going to make things hard to read by putting whataboutism caveats in every other sentence so just take that as given or insert them in yourself every other paragraph via the power of your imagination.

It’s easy to assume this article is talking about GM genius. Take it for granted everything in this article was an outcome of everyone at the table and when anything learned should only be applied to me.

How to do this?

This second part presents a unique challenge, as what defined the campaign in actual play was an intersection of play, system and the setting of stakes. This leaves the article open to just being a sequence of ‘game stories’ which isn’t the intention.

To avoid it descending into a lengthy series of game stories I’ve tried to use diagrams and structures to keep things to the key points. This means game events and system details are described with as much brevity as is possible while still serving to demonstrate the point being made.

I hope I’ve succeeded. If you want optional background reading you can find the session notes and the article on completing a campaign.

Key Moments

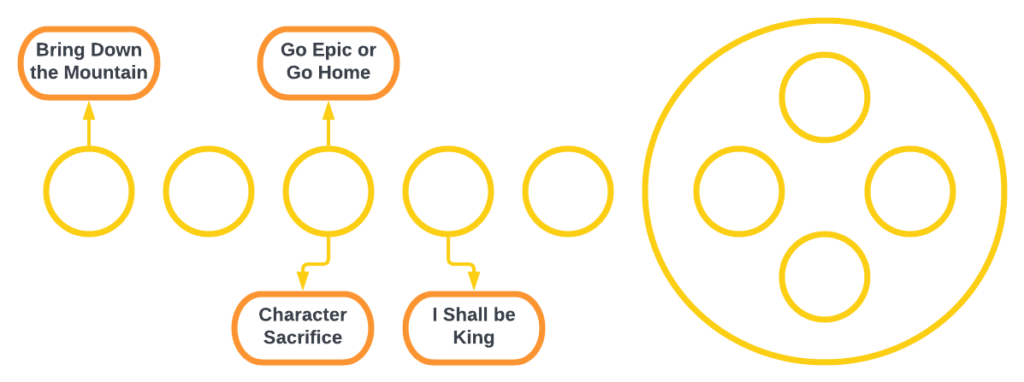

I’m going to use key moments to demonstrate how the campaign was defined by actual play. The key moments are shown below in the diagram, which is taken from the concept of planning through structure in before the dice dropped.

These moments aren’t examples of ‘we did not know we could do that‘ but more moments when a confluence of actual play, authoring decisions and the system came together to shape the campaign moving forward.

These are all from phase one of the campaign.

Bring Down the Mountain

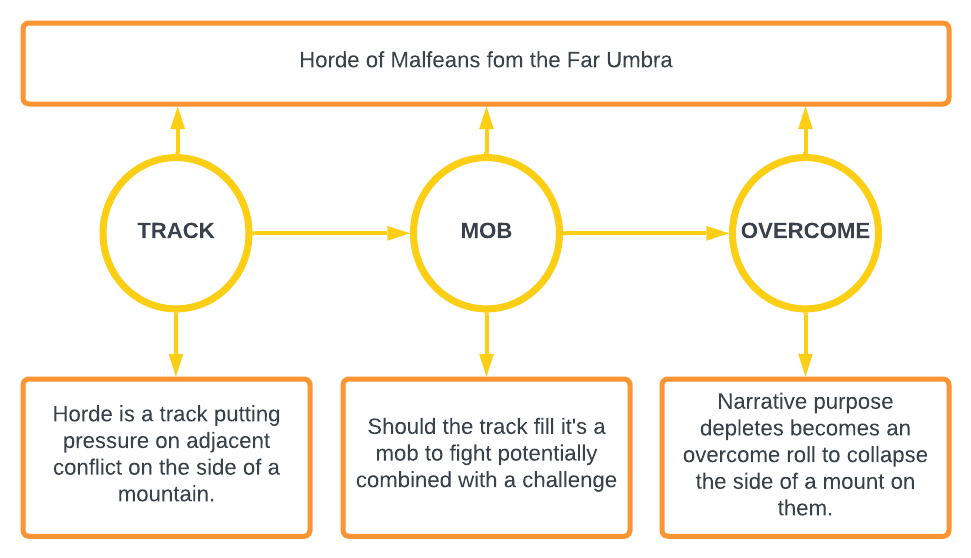

A key moment was when we shaped how the system represented something in the fiction in multiple different ways during a very short period of time.

A horde of malfeans (think the horde from The Great Wall) went from a track (it fills up over time, also like a clock from Forged in the Dark) to represent an oncoming threat as the characters dealt with the primary conflict on the side of a mountain. If the track filled the horde would have become an actual conflict with them being represented as a mob. Once they got to the top of the mountain the oncoming horde was superfluous to the narrative. A player authored it as an overcome roll (a single skill check with a desired outcome) to bring the side of the mountain down on the horde with his mythical demon axe.

The occurrence was A threat in the game was represented in three different ways in the rules over a short time period.

The outcome switching how the rules represented the fiction dynamically and in the moment became a regular tool in the campaign.

This had two main impacts on the game moving forward. It was a reminder of how flexible and dynamic things are when representing things in fiction with the rules. It wasn’t the case that elements in fiction have to have one, single system truth that always held.

It also reinforced, as would events later, that we are going more epic than even we initially imagined.

Go Epic or Go Home

It’s true the first session was pretty epic, but something really kicked in on the third session. If any single session defined the tone and nature of the campaign moving forward it was session three.

Session three just came together. I’d been thinking around it for a while, bringing it through the distant, soon and now planning horizons. Ultimately, it ended up being this epic descent to the base of The Underworld, descending down the Veinious Stair, through the Malfean Labyrinthe, across The Labyrinthine Bridge and to the Maw of Oblivion.

It had music. It had grand, melodramatic yet authentic drama. It had sacrifices which we’ll deal with next.

The occurrence was descending into the underworld took on a different level of intense drama mixed with an almost operative level of epic.

The outcome was it established ‘epic scale’ does not remove intense drama and that fully opened the gates to the scale the campaign would work at.

We moved forward from session three with the game operating at a substantially more mythical tone, without losing any authenticity or intimacy. The players made decisions with this tone in mind and I started to just go bold all the time with respect to situations.

The Character Sacrifice

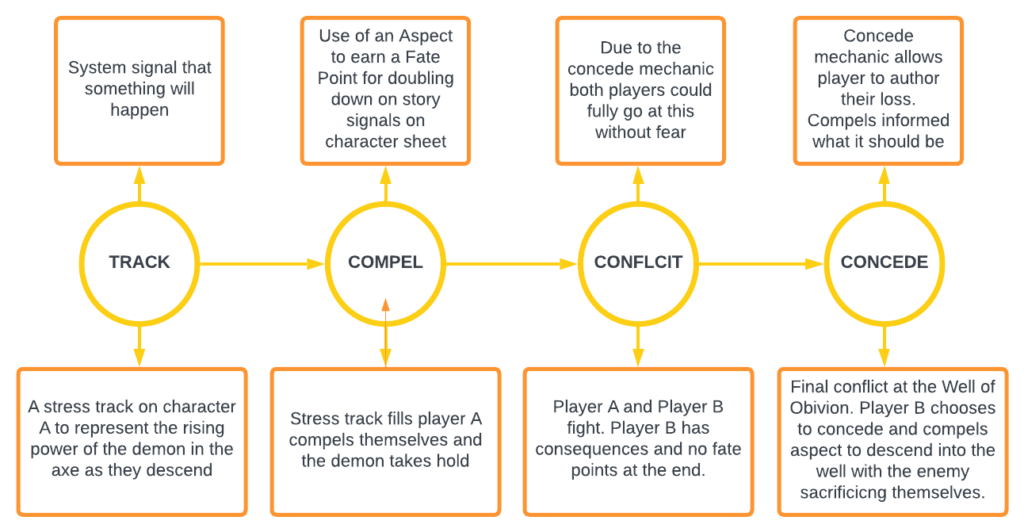

A key moment in session three saw signals and layered authoring define the campaign moving forward and shaped it in unique ways.

It was a perfect moment of how tracks can be used to send signals, how compels are the heart of the Fate system to drive the story based on WHO the characters are and WHAT their story is and the use of the concede mechanic, which to some is a ‘characters cannot die rule’ but often results in a clutch story moments better than the low hanging fruit of the GM being able to call a character dead.

The occurrence was signals, system and player authoring came together to create an awesome moment.

The outcome was it transformed the shape of the campaign and this key moment and set the campaign on the road of delivering on its intended themes.

At the point the player chose to sacrifice their character it felt narratively right despite the fact it was pure play to find out based on signals, system, stake setting and player authoring. It only happened because of a combination of factors that couldn’t be predicted yet were still intentional.

That was the pure beauty of it.

Yes, all this could have happened just by players deciding to do it without the system elements, but that’s not the same, as the system elements do something that is genius: it feels unexpected yet inevitable at the same time.

This part of the campaign is worth noting not only because it’s another example of how an intentional story comes about by discovery but also because it was a pivotal shift in the campaign. One character suffered guilt over this until his spotlight and another made a radical choice that came from ‘nowhere’.

I Shall Be King!

A key moment in session four was when a player totally surprised me, and I suspect everyone by making a bold character choice that came from ‘nowhere’. This certainly happened in session four.

The occurrence was out of ‘nowhere’ a player made a play to lead and reform the Get of Fenris werewolf clan and the Werewolf Tribles.

The outcome was signals work as this decision wasn’t out of nowhere it was in response to layered signals which begot events and decisions.

This demonstrates how signals are important wherever they are coming from as people absorb them and react to them. While this seems like a bold decision from ‘nowhere’ it isn’t: –

- The relationship between people, ideas and institutions was signalled (session zero)

- It was signalled that the future leader of the werewolves had sacrificed himself (via aspects)

- The fact the werewolves might have failed themselves was a clear theme

When you take all these things on board, was it really a surprise that the player of the younger brother of the actual leader of the Get of Fenris made a power play? Once it was chosen, absolutely not, it was genius.

I could wax lyrical about how this delivered on the tone of the campaign by bringing the historic failure of the werewolves into a reforming future and changed things going forward but I want to focus on something else. I went into the game with some sense of explicit signals being important via aspects as Fate aspects are a permission and a signal. At this point, a different theory was formed and that is the it’s all about signals theory and all the tools we use are about establishing and layering those signals. It’s how the game progressed moving forward and it became a more conscious tool.

How, what and why

One of the elements I was personally playing with going into the campaign was how to handle the HOW, WHAT and WHY of the campaign and how this related to my anxiety and having an intentional story that at least had some chance of feeling authentic and intimately satisfying.

The reason being, I felt it was all about the WHY and the HOW and WHAT were of lesser importance. The story is the WHY, the rest is just trappings to explore it in an exciting way? This certainly proved true for me and it’s now a principle I hold to.

The way the HOW, WHAT and WHY was managed became an even bigger part of how I approached the campaign than I appreciated. This is whas happened as I doubled down on the idea: –

- Leave more of HOW things are done to the players

- Focus on WHAT rises to meet them instead

- Layer everything with the fabric of the WHY

- Seriously play to the WHY

As the sessions progressed I concerned myself less with HOW the players found the situations and I just had them as the WHAT of what might happen. If they did something completely different I knew WHAT to bring in to rise against them as antagonists even if it changed shape a lot.

The majority of the time they found much cooler ways to navigate around than I’d thought of anyway, so I just stopped worrying about how they would.

Now, you might say this sounds very random? It is certainly relatively railroad free. There isn’t a plot as such in terms of HOW things should happen. The story is in the WHY things are being done as that is where the emotion is. Some systems even structure and mechanise this, as that is what Forged in the Dark is essentially doing (but that’s a different topic) – it mechanisms the HOW and WHAT elements, it has less authority on WHY.

Onward with the campaign

I could go on and make this article even longer than it is currently as there are obviously clutch and interesting moments across the campaigns length, but these are the ones that shaped the game for its length.

The key benefits of this campaign to me were: –

- I enjoy planning. I need to plan. It gave me a way to do it with no railroading

- It gave me a way of just constantly layering in signals that would get results

- It allowed us to have an intentional story authored by all with no railroading

- It felt like something we all created, or at least it did to me

- I finished a damned role-playing campaign after a big gap

I also achieved the goals set out in Before the Dice Dropped. It was a win all round.

And, Finally…

While writing this article it has felt self-indulgent. I’ve been hit with bouts of why would people want to read about this? Extended moments of imposter syndrome. I nearly stopped doing it numerous times as all this intersected with the effort. You get the idea.

The reason I kept with it was simple. We hear campaign GM’ing advice on social media all the time. We even link to articles about how things can be done, but we rarely see an attempt to describe ‘here is campaign X and how those methods were applied and explored and emerged’.

This is an attempt to do that. I hope it was useful.