When it comes to the actual play of tabletop role-playing games one thing is critical for me above all else is: the meaningful why. This is because the meaningful why, ideally layered throughout play, is my reason for playing and it is where the story is at. The challenge is, while I can enjoy actual play with different degrees of this, I really struggle when it’s virtually not there. Maybe you do to?

So, here we are, what actually is the meaningful why? How does it relate to the roles at the table and how can things be unbalanced to the point it doesn’t exist? Read on.

What is a story?

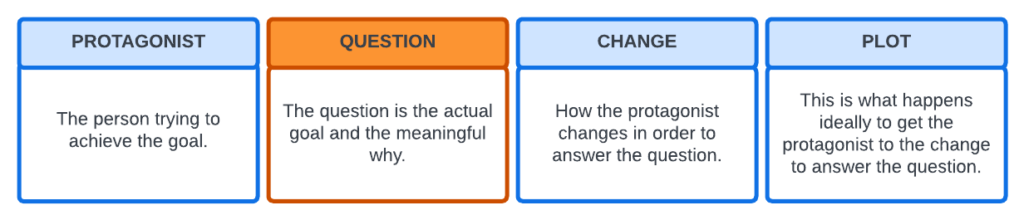

In The Railroad Myth, we put forward the argument that contrary to some popular belief having an intentional story in a role-playing game does not have to involve railroading. To demonstrate this we used the model of what constitutes a story from Wired for Story by Lisa Cron which defines a story as ‘what happens to someone who is trying to achieve a difficult goal and how he or she changes as a result’. We also discussed what it meant in role-playing game terms.

This is broken down above and you’ll notice the first three are in the domain of the player and even the plot pillar can be about playing to find out and shaped by player action and authoring. This article is about the importance of the meaningful why inherent in the question pillar.

The Protagonist why

Ultimately, we are moved to action only by emotion. That’s because action is emotion.

Mark Manson, Everything is F*cked: A Book About Hope

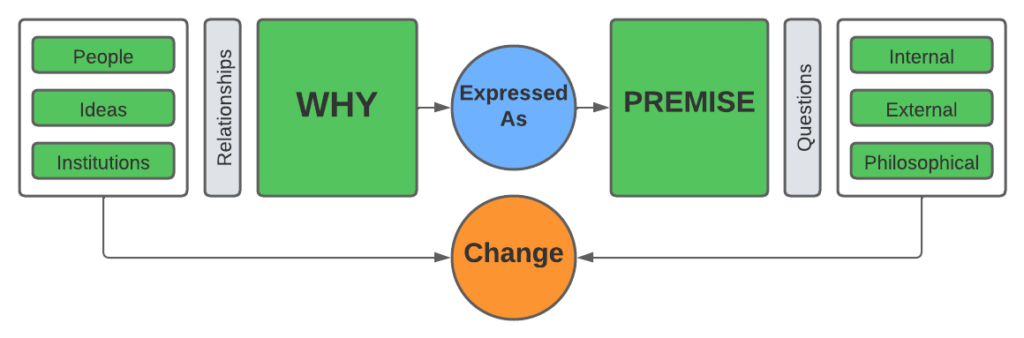

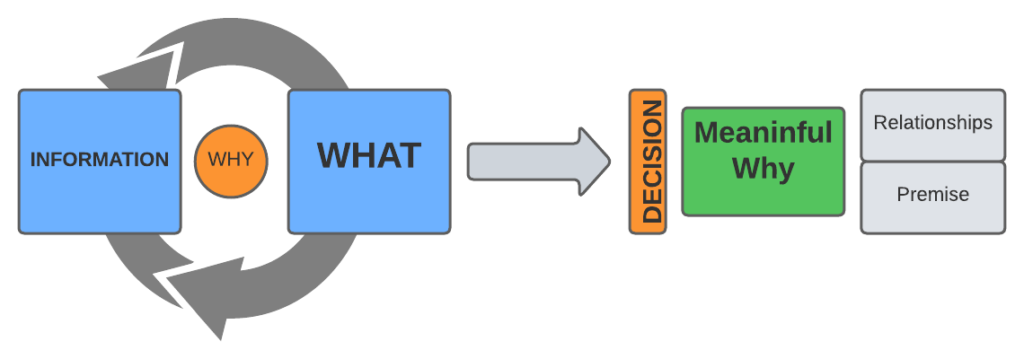

When I’m a player what I’m attempting to do and support others in doing is represented below, which we’ll break apart in this section.

The short way of describing the above is the protagonist is a collection of relationships with people, ideas and institutions which gives a meaningful why and that is expressed as the protagonist’s premise in the form of an internal, external and philosophical question.

It’s no surprise that my short character backgrounds are a bundle of such relationships and situations to support the premise of my character. The important thing is I try to make this as explicit as possible within the context of the group and the system.

Then the game is one of driving change in the relationships and answering the premise to drive change in the protagonist. The result is intentional, play to find out story similar to the definition we outlined in what is a story earlier.

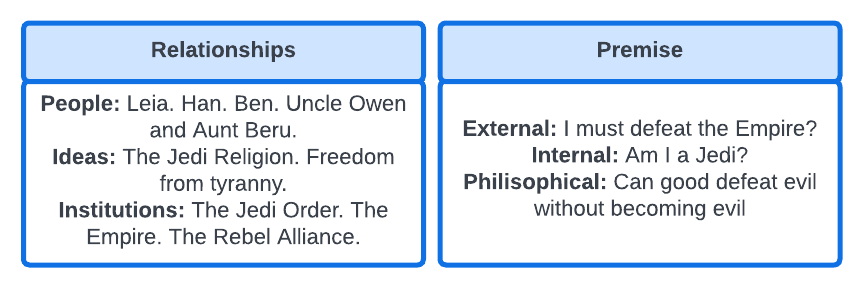

Let’s try and demonstrate this with an actual example and we can build on our use of Luke Skywalker from The Importance of Premise.

This is one take, and the relationships could be better described, but it’s Luke Skywalker and brevity is our friend here, but you can already see how this pans out by looking at the original Star Wars trilogy.

Luke is driven to change when his relationship with his Aunt and Uncle changes by their death at the hands of the Empire? He faces pivotal questions around his philosophical question in the final duel in Return of the Jedi? It could be said the reveal of Darth Vader as his father changes his philosophical question to can my father be redeemed? He faces his question am I Jedi in the whole final act of Empire Strikes Back when he chooses to leave Yoda to rescue his friends and faces Vader? Similarly, he was combative discussions with Han’s player at the end of Star Wars because of the clash of their different relationships around fighting against tyranny (and Hans’s player decided to come around, obviously driving a change there).

I am sure the list goes on, you can probably think of more and even take this forward to how these things have changed by The Last Jedi.

Player layering of the meaningful why

Imagine if all the players had similar outcomes and goals as those outlined in the protagonist why however they were doing it? And every player was consciously aware of them?

It’s basically a feedback loop of epic proportions as the feedback loop of relationships, premise questions and protagonist change happens between characters. Do you want meaningful scenes between characters similar to those in books? This is what they are about, one character’s drive for change and the things that support it interfaces with another resulting in a different journey for both.

This is why I like systems that allow premise-like items to be on the character sheet and interacted with in the game and the rules. Fate aspects are my favourite. Dungeons and Dragons, so we included the big player, has the personality, ideals, bonds and flaws set up but I find it’s rarely used or used in a way that has little actual impact.

This leaves us with one larger question, how do we layer in the meaningful why to the whole of actual play?

The simple statement

In order to help with what we’re going to discuss next it’s worth asking if we can we condense what is happening at the gaming table to a simple phrase for the purpose of this discussion?

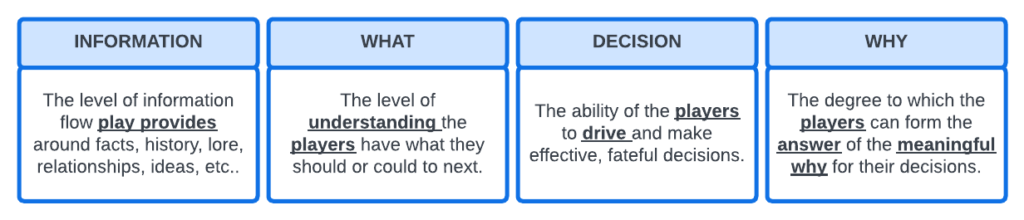

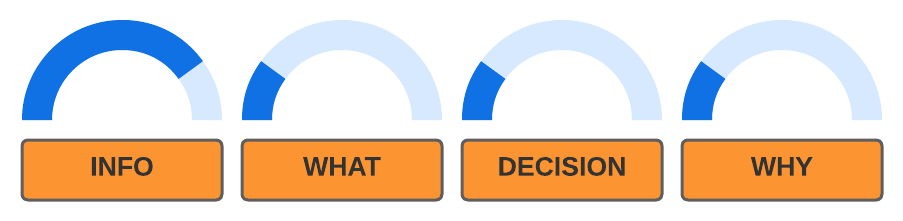

Provide INFORMATION to understand WHAT to drive a DECISION to answer WHY

The argument is this statement covers quite a lot of things that happen at the gaming table as well as some things that can go wrong if you get the balance incorrect.

What’s actually happening is fleshed out a bit in the table above, which provides a brief explanation of each of the four elements of the phrase we’ve adopted. It’s worth noting this is a simplified way of showing that how the table operates in a game of high-player authoring is all about managing and communicating clear signals.

GM Layering of the meaningful why

Disclaimer: For brevity, this section refers to the GM a lot, in truth a lot of it applies to players when there is a lot of player authoring and GM in the player’s chair activity going on.

Even in a game with a lot of player authoring the GM can control a lot in terms of how they respond. On that basis the meaningful why can either be further levelled up by the GM or stifled due to what they choose to focus on and respond to.

Basically, while there are exceptions, everything should be layered with meaningful why.

Imagine if the above was true. Whenever the GM delivered information around a situation, an NPC or both it was layered with information that had meaningful why and clear in terms of player action allowing them to transfer that into decisions to drive their meaningful why? Gold.

If we continue with our Luke Skywalker example, the GM has helped facilitate a clear what loaded with meaningful why around the danger of his friends, instantly the player has a decision born from that information and how that plays directly into their meaningful why. Does he leave his Jedi training or not? The aim should be to facilitate challenges and questions to their meaningful why.

This doesn’t even have to be direct, the events in the campaign that happen around the players should be layered with their own meaningful why as well. Why? Because that gives the players the emotional grit to self-author their meaningful why in relation to it! Events without an emotional element are much harder to do this with as there is no feeling attached. This is because the relationships between people, ideas and institutions in your situations and non-player characters are things the players can interface with just as well as they can their fellow protagonists.

It’s probably also what makes them care.

This is what I attempted with my last campaign, with every situation having relationships around people, ideas and institutions. The whole campaign was pinned on it, with the goal that the events would have some level of emotional resonance. Achieving that effectively is a delicate balance though and sometimes we get the balance wrong.

Unbalancing the why

If we discount for a second a style of play in which not focusing on the meaningful why is the intent, which is all well and good, can we assume a lot of the problems around layering in the meaningful why are about when things become unbalanced within the simple statement we established?

I think we can.

High Infomation, Low Decision

What’s happening here is a lot of information is being presented but it’s not resulting in the players understanding their options and in turn what decisions they can make. At this point even people who are trying to focus on the meaningful why might be at a loss of how to apply it in actual play to events?

An example, when things feature a heavy investment in the setting, you can get a lot of information about the history, people, and lore and maybe the odd Elf might sing you a song while you eat a meticulously described meal but if it doesn’t result in an understanding of action with a way to see or apply a meaningful why who cares?

Yes, that’s a bit harsh, but the truth is all that may be great, but it has to be balanced with action and decision at an overall execution level, individual scenes might focus entirely on the immersive information, but it can’t be all about that.

If this was a meal, you’ve been given something expensive, large and rich but you’ve now been bludgeoned into a food coma and incapable of any interesting decisions.

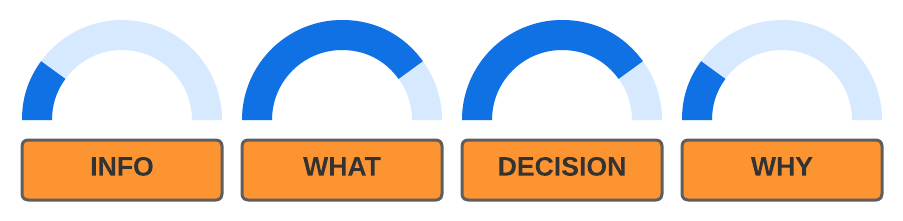

Cliff Notes Information, High Decision

This sounds good? The height of efficiency. You’re not getting too much information yet it’s given you a high understanding of what, which in turn is allowing a high amount of decision. The challenge is it’s so damned efficient it’s happening without any meaningful why as that might slow down the machine!

The immersion and feeling of the environment is potentially low to non-existent due to the efficiency of information. It’s possible things are so efficient with so little information you’re almost just being told directly what to do next or given it like a bullet point list with little in world feel.

In this set-up you better hope what is happening is damned exciting beyond measure as there is little else to hang the experience off. The best you can hope for in this situation is it’s a bit like ‘what the hell’ event TV at best. This is hard to maintain and gets naturally tired over time. As an example, the events in the Star Trek: The Next Generation episode Best of Both Worlds could be made naturally exciting to create a brilliant episode, but the true legacy of it is the impact on Ryker’s meaningful why over taking the Captain’s chair and Picard’s re-shaping of his meaningful why due to losing his humanity when Borged.

If that wasn’t true you literally have something so efficient at this point it’s a Mcdonald’s meal, probably stuffed down while in a rush while also driving. If momentarily exciting it’s one of those unique and exciting meals that is hard to duplicate on a continual basis.

Getting the balance right

I could go on with different patterns and fancy infographics but you get the idea. The important point is how you avoid a catastrophic imbalance. I believe there are some good principles to follow.

Explicit meaningful why. Be explicit about every meaningful why. In the player domain have them as things that can be interacted with at the level of the rules on the character sheet. If that’s not possible have each player make their protagonist’s meaningful why clear in session zero. These things should be known at the player level which is different to the character level. The GM should make meaningful why’s clear (as should players) when presenting information in descriptions and how non-player characters speak about things. Make it explicit via every tool possible in an organic, which does not mean obscure or hidden, way. This is also why ‘meta-gaming’ is a good thing when it’s about explicitly discussing what’s going on with a character.

Grow into it. With regards to premise, you can start small and/or discover things through actual play. Maybe you start with a simple issue like your character is obsessed with revenge? Maybe you start with nothing and over the course of the first few sessions or so you fill out each question as your thoughts take form. Nothing is prescriptive, all that is really important is the meaningful why becomes something explicit and actionable across the table.

Focus on outcomes. Always be clear of your outcomes. What are the outcomes for the campaign? What are the outcomes for the session? What are the outcomes for the scene? These should not be pre-destined outcomes, but strategic in application and principle-based in approach. Basically, you have a strategy for what you’re doing. By focusing on outcomes you can ensure your decisions are contributing to your outcomes. The meaningful why is an approach to ensure your game has emotional weight. If you’re wanting that outcome decide purposefully on what you’re doing with that outcome in mind. I joke that tabletop role-playing games, if you’re being intentional about what you want, have some similarities with consultancy engagements. I am only half joking. Be purposeful.

Saturate situations with why. Saturate the game with meaningful why, it’s everyone’s job. It doesn’t have to be overwrought or hopelessly melodramatic but because most events in your game will be outcomes of the wants, needs and desires of actual people then, believe me, they are layered with meaningful why you’re just choosing not to focus on it (which is also fine if linked to your outcomes). Ideally, shape this layering of the meaningful why in ways that will allow the players to hook into them to further shape, develop and take forward their premise questions.

Consequences are everything. Quite often a litany of information is not what’s important it is clarity of consequences. Never lose sight of the clarity of consequences. Why? Because consequences drive decisions. Decision drives changes in relationships and premise. Yes, the history and facts of an impending conflict between two nations may be fascinating but it’s the consequences in the situation that will drive any decisions. This helps get that balance right between information and clarity of what.

Scene types are your friend. Not all scenes are the same. When discussing narrative velocity we established outlined three types of scene: conflict, transition and exploration. As long as your game doesn’t have too many exploration scenes to the point you tip into high information and low decisions they can be used to impart that rich world and allow for some slow soak immersion. Why? Because it’s happening in a way that isn’t blending that volume of ‘colour information’ with conflicts that drive change and transitioning forward. It’s in its own space where everyone can relax and enjoy it for what it is.

Do the damned scene. This is the killer. Do the scenes that drive that change. Whether the GM starts the scene or players do. Do the damned scenes. What happens a lot, even in games that aren’t as explicit about the meaningful why’s of the player characters, things come up that are worth addressing and people nod and don’t create the scene. It becomes a sort of passive undercurrent. Create the scene, put those scenes in that exist in books. Just do it. Yes, the atmosphere and environment has to exist where this is wanted and doesn’t feel self-indulgent, but do your best!

Get to the decisions. While you don’t want to be so aggressive you’re unbalancing things you do want to get to the fateful points of decision. Drive the game to fateful decisions. Use the dice to drive things in interesting and unexpected ways by rolling only when it really matters and both outcomes are interesting. Play to find out. This is because if you’re transition to scenes where important things are resolved and issues dealt with you’re not tackling the need for the protagonists to enter situations that support their need to change.

And, Finally…

The meaningful why isn’t just something that I look for so I can really fire on full cylinders in a game, it is the basis on which an intentional story, that can be fully explored by play to find out, can be the outcome of a game. It is the distilled ingredient of scenes in your game that are like the ones in other media, as this is what those scenes are about (and that’s the important thing, the content, not if they are as well acted or as well written).

The challenge is implementing a meaningful why takes purposeful intent and the correct balance across information delivery to understand what is going on so it can be translated into decisions focused on answering a protagonist’s premise questions. The balance of these things can be off which makes this loop more challenging. I’d even go as far to say many games focus on the wrong areas in this loop, which may or may not be fine depending on the true outcomes you want.

Hopefully, this article helps in some way, via methods you choose to adopt, to add meaning, emotion and fateful conversations at the level you want in your game.